NDI has been a leader in democracy and technology, but to meet the challenges of our time, it is increasingly clear that the Institute needs to integrate technology into every program we undertake. In an article for the Journal of Democracy titled Rejuvenating Democracy Promotion, author Thomas Carothers, an expert on international democracy support, advocates that technology needs to be put “at the center of concepts and practice in the field of democratic development and assistance” going forward.

To meet the moment, NDI developed a course on technology for democratic development, titled DemTech 1000. The first-of-its-kind certification course for NDI staff is intended to empower staff with a basic foundational understanding of how to utilize digital technology effectively and counter its negative impacts. The course covered the principles for digital development, defending political discourse online, human-centered design, cybersecurity, budgeting for technology, and technical project management.

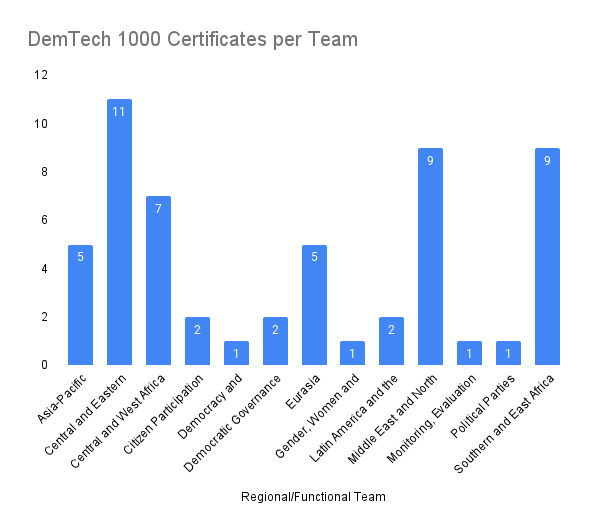

To date, 63 staff from 23 countries have completed the DemTech 1000 course in its various versions. Assessments of the course have been positive and highlighted that the topics were helpful and represented new information that NDI staff had not previously explored. The sessions on human centered design and cybersecurity stood out as particularly valuable, and all respondents who attempted to finish the course said they would recommend it to colleagues.

“It was a great opportunity to gain a deep understanding of several topics related to program management and using technology in our programs,” said Mohammad al Basoul, a field coordinator in Jordan.

Taking lessons from NDI programs in Latin America, the latest offering of DemTech 1000 leveraged the open-source learning management system called Open edX. Open edX has been a very successful component of NDI’s work in Latin America, where online courses have become a key element of the Red Innovacion program. Thousands of students have completed coursework in Spanish on topics ranging from political leadership, women’s political participation, strategic planning for political parties and more.

Several participants in the course suggested a hybrid model for future versions of the course, noting that the live components of the course were most rewarding. While the asynchronous and self-paced course was appreciated given heavy workloads and timezone challenges, staff expressed a desire for more opportunities to interact with other NDI colleagues from around the world via the course chat or more live sessions.

“Even though the asynchronous and self-paced nature of the course usually serves as an advantage, I do believe that several live meetings along the study course might have been helpful,” said Shalva Dekanozishvili, a program assistant in Georgia. “In this sense, the meeting with [former Wikimedia CEO] Katherine Maher really was a highlight.”

Paul-Emmanuel Bakayoko, senior program manager in Cote d’Ivoire, expressed a desire for more professional development opportunities. “Please continue to reinforce staff capacity by examining practical projects,” he said.

More work needs to be done to ensure that the entire Institute is equipped with basic knowledge about navigating technological opportunities and challenges. To that end, the course will be revised with feedback from those who took the course, and it will be offered again to a new cohort of NDI staff in the summer of 2022.

This blog was originally posted on Dem.Tools at https://dem.tools/blog/demtech-1000-course-puts-technology-forefront-democratic-development-ndi-staff